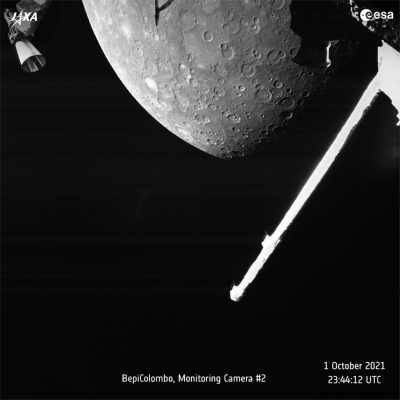

The ESA/JAXA BepiColombo mission has captured its first views of its destination planet Mercury as it swooped past in a close gravity assist flyby last night.

The closest approach took place at 23:34 UTC on October 1, 2021, at an altitude of 199 km from the planet’s surface. Images from the spacecraft’s monitoring cameras, along with scientific data from a number of instruments, were collected during the encounter. The images were already downloaded over the course of Saturday morning, and a selection of first impressions are presented here.

“The flyby was flawless from the spacecraft point of view, and it’s incredible to finally see our target planet,” says Elsa Montagnon, Spacecraft Operations Manager for the mission.

The monitoring cameras provide black-and-white snapshots in 1024 x 1024 pixel resolution, and are positioned on the Mercury Transfer Module such that they also capture the spacecraft’s structural elements, including its antennas and the magnetometer boom.

Images were acquired from about five minutes after the time of close approach and up to four hours later. Because BepiColombo arrived on the planet’s nightside, conditions were not ideal to take images directly at the closest approach, thus the closest image was captured from a distance of about 1000 km.

In many of the images, it is possible to identify some large impact craters.

“It was very exciting to see BepiColombo’s first images of Mercury, and to work out what we were seeing,” says David Rothery of the UK’s Open University who leads ESA’s Mercury Surface and Composition Working Group. “It has made me even more enthusiastic to study the top quality science data that we should get when we are in orbit around Mercury, because this is a planet that we really do not yet fully understand.”

Although the cratered surface looks rather like Earth’s Moon at first sight, Mercury has a much different history. Once its main science mission begins, BepiColombo’s two science orbiters – ESA’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter and JAXA’s Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter – will study all aspects of mysterious Mercury from its core to surface processes, magnetic field and exosphere, to better understand the origin and evolution of a planet close to its parent star. For example, it will map the surface of Mercury and analyze its composition to learn more about its formation. One theory is that it may have begun as a larger body that was then stripped of most of its rock by a giant impact. This left it with a relatively large iron core, where its magnetic field is generated, and only a thin rocky outer shell.

Mercury has no equivalent to the ancient bright lunar highlands: its surface is dark almost everywhere, and was formed by vast outpourings of lava billions of years ago. These lava flows bear the scars of craters formed by asteroids and comets crashing onto the surface at speeds of tens of kilometers per hour. The floors of some of the older and larger craters have been flooded by younger lava flows, and there are also more than a hundred sites where volcanic explosions have ruptured the surface from below.

BepiColombo will probe these themes to help us understand this mysterious planet more fully, building on the data collected by NASA’s Messenger mission. It will tackle questions such as: What are the volatile substances that turn violently into gas to power the volcanic explosions? How did Mercury retain these volatiles if most of its rock was stripped away? How long did volcanic activity persist? How quickly does Mercury’s magnetic field change?

“In addition to the images we obtained from the monitoring cameras we also operated several science instruments on the Mercury Planetary Orbiter and Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter,” adds Johannes Benkhoff, ESA’s BepiColombo project scientist. “I’m really looking forward to seeing these results. It was a fantastic night shift with fabulous teamwork, and with many happy faces.”

BepiColombo’s main science mission will begin in early 2026. It is making use of nine planetary flybys in total: one at Earth, two at Venus, and six at Mercury, together with the spacecraft’s solar electric propulsion system, to help steer into Mercury orbit. Its next Mercury flyby will take place on June 23, 2022.

Comments

Post a Comment